Translated from the Polish by Jan Pytalski.

It was seventeen degrees below zero Celsius and the streets were empty. Water as green as tropical algae dripped across the street.

It was coming from the gate of a house that had been rebuilt after the war, including its overall sense of narrowness required three or four hundred years earlier by property prices in this prosperous port city. The city was rebuilt to restore its previous look, sometimes down to exact details, following a naive belief that that would turn it back into what it used to be before the war. It was an exercise in fidelity without purpose, an empty gesture of men in love with history. The water kept flowing through the gate from this tenement house, from the laundry room, and froze in the square, creating a puddle the color of shower gel that smells of bergamot and verbena—or that was what it brought to mind because it was odorless. Women were evacuating the laundry room, grabbing whatever was at hand, some papers, packages. Nobody paid attention to the artificial Gardens of Eden congealing in the freezing cold, as if the parrot-green slick was an everyday occurrence in these parts. “The cold burst the pipes again,” a woman who saw my amazement told me. “They color the water used in the central heating here like that.”

I went to the almost-empty restaurant, just me and two other young men in suits, from whose table an avalanche of stories about money kept rolling my way. The owner’s son played the role of waiter: he would approach to ask if we needed anything, but we only wanted to sit for a little while with our tea. The cook watched a game on TV in the back, the waiter was bored and soon fell asleep behind the bar; he’d wanted to close for some time now. I was overcome with pain; I could barely sit. I kept counting: how many steps left to the hotel, how many floors to the room, how many hours till morning. Outside there were no cars, no pedestrians—there was just a great silence covered in snow, interrupted only by seagulls. The artificial city, rebuilt in its own image, and wherever men lost their zeal to rebuild they left deep holes looming in the ground. They had been looming like that since I can remember. The snow-covered city waited for its Huns, who come back every summer to take possession of the streets. To kill time, they listened to the radio, and on the radio the city felt alive, as if they were talking about a completely different place. Anyway, at least nobody was in the downtown area; it was silent and you could hear only those seagulls. Taxi drivers kept listening about the accidents, road blocks, about this complex organism, a wild termitary. In the meantime, from above, from a plane, you could see empty spaces, land turning into sea, both gray and under a layer of snow.

I had come here every year since I can remember. We would walk the same streets, as if only to see what had changed. From the train station, through the underpass, on the right a music store, past the store a right turn, a deli, a tower; in the market hall we looked in awe at the smoked eels and all the merchandise from forbidden worlds, and finally the city made of reinforced concrete, not Danzig, or Gdańsk anymore, but its fairly faithful copy created out of the need for continuity. A lie made of concrete and brick, half a hole in the ground and half houses almost identical with the original, but flat like modern apartment buildings, with crooked carpentry, a mix of local baroque and social realism. The old town in my own city was the same, leveled to the ground in 1945 and later rebuilt.

“Rebuilding” is a key word in my part of the world, similar to other words like “war,” “besieged,” “murder,” like “liberation,” “exile,” “escape,” like “cemetery” and “displacement,” like “Regained Territories” and “post-German houses.” Here, if you dig a little deep- er, it turns out to be fake, not original, a couple dozen years old at the most. Gdańsk was one of those spots on the map, also Wrocław—a field of rubble, Warsaw, of course, and later Berlin and Dresden, also Nuremberg. Or the castle on the island in Troki, a masterpiece of forgery, taller with every passing year, and newer. The first time I was there it was merely a ruin among the bushes; the last time I visited it stood tall and brand new in the middle of Troki’s frozen lake on which cars and horse-drawn carriages kept driving back and forth in the cold of March; so similar to Malbork and other places like that, rebuilt from scratch. These cities, those places need the cover of snow to hide their architectural absurdities. They came into being because of the belief in continuity, in a thread connecting then with now. That’s where my distrust of other cities comes from—cities better equipped with souvenirs, cities spared by misfortune or simply indifferent to the Middle Ages, taking down their remains without a blink of an eye—my distrust of Paris with its mad builder and demolition expert, Count Haussmann, with its crazy mayors, or to a lesser extent, my distrust for nineteenth century Krakow, leveling its moats, taking down its city walls and towers. There was an obligation in me, in us, to sit in all the churches until the last painting was seen and immediately forgotten. There was a need to ride across the world along the thread unwound by the Baedeker.

I came back to the hotel and spent the rest of the night in a torpor. On our way to the airport we didn’t see a single car. The taxi driver was listening to the blasting radio, and on the radio the city felt surprisingly alive again, completely different from what was outside our windows, impossible to recognize.

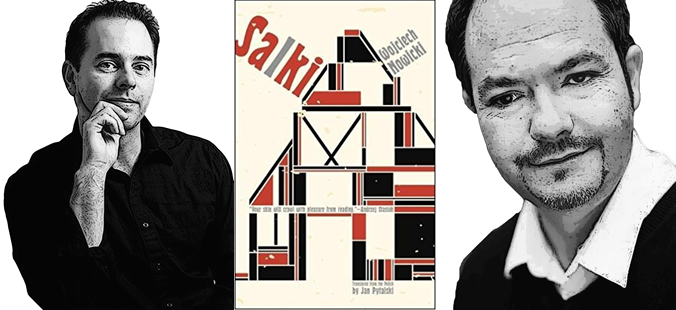

Wojciech Nowicki is a Polish essayist, journalist, critic, photographer, and even writes a culinary column. He is also the co-founder of the Imago Mundi Foundation devoted to promoting photography. Salki is his first book to be translated into English.

Jan Pytalski is a graduate of the American Studies Center at the University of Warsaw, and has an MA in translation from the University of Rochester.

This excerpt from Salki is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2013 Wojciech Nowicki. Translation copyright © 2017 Jan Pytalski.

Photo: Wojciech Nowicki, Private

Photo: Jan Pytalski, Private

Published on May 2, 2017.