This is part of our special feature on Sustainability & Innovation.

We are in a remarkable period of urbanization of the planet, as the percentage of the world’s population living in cities continues to grow, likely rising to 70 percent by 2050. However, it is not clear that we are creating cities and urban spaces that inspire, that invoke joy and wonder, and that nourish the soul. In many parts of the world, the cities being designed and built are antiseptic, detached and disconnected from the ecosystems in which they sit. Residents are profoundly disconnected from the nature that has sustained our bodies and spirit for millennia.

This is the essential insight of the Biophilic Cities idea and movement: that we need nature, we need daily, hourly, frequent contact with the natural world. Nature is not an optional design element, but an essential ingredient in leading happy, healthy, and meaningful lives. Nature, moreover, should be understood as a destination, as a place to visit. It should be all around us, integrated into the spaces and places where we spend most of our time: our homes and offices, our urban neighborhoods.

Biologist E.O. Wilson is often credited for developing the idea of “biophilia.” Biophilia refers to the innate affiliation we have with nature. When Wilson wrote the seminal book Biophilia, in 1984, the evidence of this innate connection was fairly limited. Today, more than three decades later, the evidence is robust and growing. We know that a walk in a forest (what the Japanese call shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing”) lowers stress hormone levels, and boosts our immune systems. Nature has the ability to alter our mood, to enhance cognition, and to calm the many stresses of modern urban life. There is even evidence from psychology that in the presence of nature we are more likely to be generous, more likely to be cooperative, more like to think longer-term. Nature helps to make us better human beings.

With support from the Summit Foundation, we started the Biophilic Cities Project at the University of Virginia, an effort to begin to understand how we might fuse our growing recognition of the power and essentiality of nature with the design of cities. Much of our initial work focused on a series of initial “partner cities.” These included places like Singapore, Wellington, NZ, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, Birmingham, UK, and San Francisco, among others. In 2013, we formally launched the Biophilic Cities Network, which now includes about fifteen cities. Recent cities joining the Network include St Louis (MO), Austin (TX), Pittsburgh (PA), and Edmonton, Canada.

Much of the first several years of our work have been about research: about understanding the creative and innovative ways that cities are already integrating nature into their design and planning, and the different ways that we might understand what a biophilic city is, or could be. We have been developing short documentary films about our cities, helping them share insights and experiences, and inspiring other cities. We have organized several sets of webinars (all on our YouTube channel), we have a new logo and web page,[1] have started a Biophilic Codes Initiative, and we have recently released the inaugural issue of the Biophilic Cities Journal.[2]

We build on the considerable work already completed around biophilia and the built environment.[3] The emergence of biophilic design in architecture and building design builds on essential insights: we need work spaces, for instance, with windows and natural light, with plants and views of nature. Biophilic Cities agree about the importance of designing interior living and work environments, but argue that we must go beyond that—we must think about “whole of city” nature: it is nature at the scale of the building, but also the block, the neighborhood, the larger city. It is room or rooftop, to region or bioregion, and all the spaces in between. And it imagines going far beyond the vision of cities with some parks and trees. Nature is not just to be found (and visited) in specific places in the city; rather, the city itself must be understood as a natural system—we should aspire to cities not where one can visit the park, or the garden, or the forest, but can live wIthin the park, garden or forest.

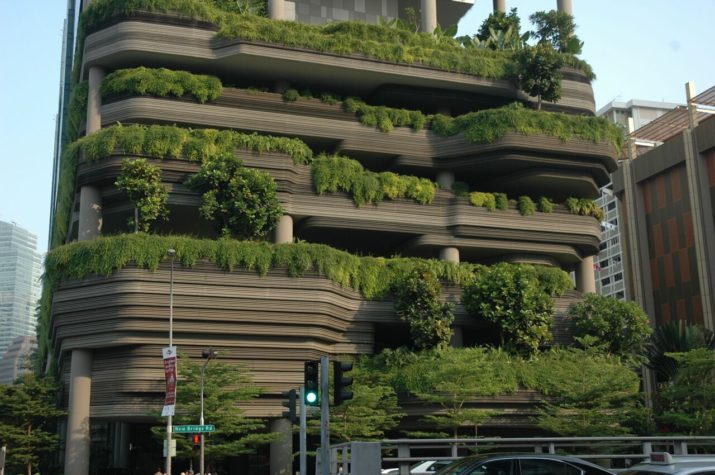

Many of the cities in our Network are embracing this more holistic, immersive view of nature. Singapore may be the best example: they have officially changed their motto from Singapore a Garden City, to Singapore a City in a Garden. This new philosophy and vision can be seen in what is being designed and built in this city. New hospitals are following the model of the KTPH, or the Khoo Tech Puat Hospital, which understands the important healing power of nature, and which puts nature at the center: there are multiple levels of green roofs, an interior green courtyard with a waterfall, even an urban farm on one roof, which includes scores of fruit trees. A more recent example is the ParkRoyal Hotel, envisioned as a hotel in a garden. It is a remarkably verdant, growing structure with draping plants and skygardens, enjoyed both by those staying there but also by the neighborhoods. Under Singapore’s Landscape Replacement Policy buildings like the ParkRoyal are required to replace, at least one-to-one, what is lost at the ground level with nature in the vertical realm. In the case of this structure ground level, nature is replaced by more than 200 percent in the form of vertical gardens. There are also many citywide programs and policies in Singapore that seek to grow and seamlessly weave together the nature of the island: a 300 km network of trails and pathways (called Park Connectors), support for gardens through a program called Community in Bloom, and a Skyrise Greenery Incentive Scheme, among others.[4]

Many of our new Network cities, or cities considering joining the Network, are drawn to this vision, and indeed are re-discovering earlier expressions of this vision in their city histories. Austin was once known as the City in a Park, and Atlanta, GA, as the City of Trees. In this sense, it can be argued that the vision of Biophilic Cities is helping cities to re-connect with and re-invigorate a vision and aspiration for more immersive nature that they might have had in the past.

Biophilic Cities also understand that cities are shared spaces, and that they harbor and support many other forms of life. Seeing and experiencing this life firsthand, from birds to ants to coyotes, enhances quality of urban life and humane co-existence is a goal and duty. Austin, Texas, is famed for its love of its 1.5 million Mexican-free tailed bats, for instance, that take up residence under the Congress Avenue Bridge every spring and summer. Edmonton, Canada, has undertaken impressive work around the idea of ecological networks, and the importance given to the movement of wildlife through the city (they have now constructed twenty-seven wildlife passages there). There are many potential moments of awe and wonder in cities, and Biophilic Cities seek to celebrate and maximize these moments.

For partner cities like Wellington, NZ, much of that nature is in the marine realm, and the city is actively developing a network of Blue Belts to complement its land-based Green Belts. Cities like Wellington, and San Francisco, increasingly recognize the need for a more comprehensive view of urban nature, one that includes the biodiverse marine realm.

Biophilic Cities recognize that nature is multisensory, and that there is value for instance in preserving and enhancing the ability of residents to hear natural soundscapes (and conversely to avoid health-damaging noise, that also masks natural sounds). Hearing native birdsong is a goal in some cities, for instance, and we increasingly recognize the therapeutic power of birdsong and other nature sounds. What constitutes “nature” in Biophilic Cities will also vary in other ways, of course. Biophilic design argues for the power of the shapes and forms of nature, and images of nature, that may not be living in the sense of a tree or bird. References to nature can happen in many positive ways, from murals, to building details, to sidewalk mosaics, among many others.

Cities joining the Biophilic Cities Network must choose and agree to monitor a set of indicators, from certain main categories. Cities must take stock of their current efforts to protect and grow nature, and indicate plans for the future. Cities must also secure a city-council adopted resolution or proclamation stating intent to join the Network and to aspiring to be a Biophilic City. The bar for becoming a new partner city is not high. We do not view the Network as another green certification system—but rather, it is an aspirational network of cities who find the vision compelling and are convinced of the need to put nature at the center (and to helping other cities in this mission, and advancing the global movement). We view the certificate awarded to new partner cities not so much as an accolade or an accomplishment, but as a statement about priorities and intentions moving forward.

One conclusion is that cities around the world are implementing a variety of strategies to conserve and protect and plan for urban nature, as well as to design-in and grow new nature in cities. San Francisco has pioneered, for instance, the concept of parklets, small parks created from two to three on-street parking spaces, an idea that has been emulated in other cities around the world. That city has also created the unusual mechanism of a sidewalk landscaping permit, which allows residents to take up some of the hard surface of the city and plant gardens. Some 2000 of these permits have already been issued.

Our new vision of nature in cities recognizes that it is partly about making room for nature, for growing new nature in small spaces. And it understands that nature will be vertically layered, finding spaces on rooftops and balconies. The Transbay Transit Center, under construction in San Francisco is an example—a new transit facility, but with a new 5.4 acre rooftop park. Another example can be seen in the proposed 11th Street Bridge Park that will join two sides of the Anacostia River in partner city Washington. Reimagining every infrastructure project as an opportunity to grow more nature in the city.

Vitoria’s story of its impressive Green Ring is well-known among European planners, but inspiring to cities in the US and elsewhere. We have taken groups of students to this remarkably natural city, visited the gardens and hiked the spaces in and around this city. The nearby nature enjoyed by residents is abundant, including the Salburua, a former airport restored back to a wetland. And the infrastructure and investments of the city allow indeed encourage residents to be outside, with more than half the trips in this city made on foot. This city, which held the European Green Capital City in 2012, continues to prove its nature bonifides by extending the green ring into the center of the city, and bringing a stream back to the surface and back to life.

How compelling is the vision of Biophilic Cities? We believe it is very compelling indeed, and the traction it has been gaining in recent months is indicative. It is compelling, I think, for several reasons. While we need cities that are sustainable and resilient (much of my own work has been on these topics) they are often framed in terms of things cities must initiate, for instance, a rapid shift towards adaptive land use policies or investments that take us away from fossil-fuels, all important goals. But what the word biophilic captures is something more about the kinds of places we want to live, indeed the kinds of places that we need to flourish and thrive and grow.

In a documentary film we made several years ago called the Nature of Cities, we interviewed Richard Louv, author of the groundbreaking book Last Child in the Woods. He said it well in that interview, recorded on the edge of a lake not far from his home in San Diego: He recalled that civil rights activist Martin Luther King once said that “any movement will fail if it cannot paint a picture of a world that people will want to go to. We’ve been failing in the painting of that picture,” Louv said. The Biophilic Cities vision and emerging movement is in large part about painting this more positive future of cities we will want to live in.

While we continue to grow the Network, there remain a number of open questions. What role will the Network play, and how will it function as more cities join? We envision a variety of ways that partner cities will help each other—including sharing codes, policies, and project experiences, hosting site visits and city-to-city exchanges, entering into agreements to work together on specific projects, and lending support (political and technical) to cities that seek to advance the agenda and push the envelope. There will be significant challenges ahead: cities will need to foster grassroots interest and support (and we are seeing organizations community-based, such as Biophilic DC in Washington, and BioPhilly in Philadelphia, forming to advocate for biophilic urban policy), and will continue to need champions within the local government, such as a mayor or sustainability director. Finding the financial resources to support biophilic planning and investments will also remain a challenge. On the other hand, there are important, new opportunities to form alliances, for instance, with those in the public health and medical communities around the healing power of nature, and those advocating urban resilience (virtually everything that can be done to make a city more natural, from tree-planting to living roofs, will also make it more resilient). We believe that the vision of Biophilic Cities—natural, wondrous, restorative cities—will inspire, guide and motivate in the direction of a new model of urbanism.

Timothy Beatley is the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, and Chair of the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture at the University of Virginia, where he has taught for the last thirty years. Beatley is the author or co-author of more than fifteen books, including Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities (recently translated into Chinese), Native to Nowhere: Sustaining Home and Community in a Global Age, and Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature Into Urban Design and Planning. Beatley directs the Biophilic Cities Project at UVA and co-founded UVA’s Center for Design and Health, within the School of Architecture.

References:

[1]www.BiophilicCities.org

[2]See http://biophiliccities.org/biophilic-cities-journal-volume-1-issue-1/

[3]Especially the work of people like the late Stephen Kellert who a major leader and did much to educate and animate many of us now working on this topic; see Kellert, Heerwage and Mador eds, Biophilic Design, John WIley, 2009.

[4]We have documented the Singapore story and the stories of our initial partner cities through a new book, Handbook of Biophilic City Planning and Design (Island Press, 2017).

Published on June 6, 2017.