Translated from the Bulgarian by Izidora Angel.

This is part of our special feature on Contemporary Bulgarian Literature.

[Saturday, December 29, 2012]

“This is it,” Georgi Sheytanov must have thought as they unfastened the shackles chaining his ankles to those of some gruff, petrified villager from Nova Zagora, and shoved him toward the dark, unlit car parked at the train station. He must have been certain it would all end that night. He’d cut and run from everything and everywhere, including the Sofia Central Prison, where his escape was but a given fact and they’d kept a watchful eye on him, not, as it turned out, to actually prevent him from fleeing, but rather from the itch to see how the infamous anarchist would do it. But how closely had they watched him, really? True to form, he stayed just long enough to incite a riot and then vanished, and life once again lay before him, whatever that meant.

Yet in that moment, at the train station at the foot of the mountain, he must have felt a deathly fatigue.

In any case…

The chains they took off, the ropes they left on, and they forced him, bound, into the car, steering the automobile up the sharp mountain road. And he would never find out what had happened to the poet, Geo Milev.

[Sunday, December 30, 2012]

The headlights of the heavy vehicle cut through the darkness ahead, only illuminating the boulders on the side of a road eroded from that spring’s incessant rains and riddled with black puddles that the car tore through, spraying the drops far and wide like precious gems. The driver took the turns up the steep road violently; Sheytanov, all knotted up in the back seat, had no way of grabbing the bronze handle on the inside of the door, and instead lurched side to side with the car.

They took him across the mountains to Gorna Dzhumaya, where his arrival was met by the same pathological slaughterers whose names had been on everyone’s lips that year—the year an undeclared, loathsome war pitted neighbor against neighbor. And it is said that these thugs then began to contemplate his verdict. But he wasn’t about to have any of it.

“Me,” he said, “you don’t sentence. Me, you either shoot or you let go.”

But who can say if that’s how it really happened? It may not be all true, but it’s certainly faithful to the truth.

[Tuesday, January 1, 2013, New Year’s Day]

Sheytanov must have known that exactly two weeks prior to his own capture, Geo Milev had already been to court and that his lawyer had conveniently not shown up on time, which had necessitated the poet to act as his own attorney—that much was reported in the newspapers. The case itself had been absurd: a poet on trial for writing a poem. The people in the dust-filled courtroom had not taken in a single word from the poet’s defense—that everything he’d written was in the name of humanity, brotherhood, and love and peace on earth, that this was an idea anchoring his entire body of work, and that the real question at hand for the Bulgarian court was: would it convict a poet for his words? But when have a poet’s words ever been taken seriously by a court? Geo Milev was convicted, and it was then, in the middle of May, as he lay low in the Balkan mountains amid the tentatively verdant forests above Kilifarevo that Sheytanov likely first read the resulting headline inside that rag known as Utro: “Guilty: Author-Provocateur of ‘September’ Poem Convicted for Instigating Class Division and Hatred!” And perhaps while reading that same paper he had also learned what the poet’s sentence had been, and who knows, maybe he’d simply groaned that a year in jail along with a twenty thousand leva fine was the lesser of two evils. The twenty thousand wouldn’t be a problem to get hold of, just as the five thousand leva bail before it hadn’t been; he had been the one to bring the money to Mila, the poet’s wife, after they’d first arrested her husband back in January. Mila had been running around in despair then, making the rounds at all the publishers her husband worked with, the bookstores and newspaper stands whose owners still owed him money—managing to collect a hundred leva here, two hundred there—all the while growing faint and nauseated with the realization she’d never actually come up with the full amount. Sheytanov brought her the accursed five thousand leva in the afternoon: ten lousy bills the color of dirty violet . . . Her eyes, behind frames thin as a spider’s web, had looked distraught, and he, see- ing her so scared, had lied for the first time in his life; he said everything would be all right. But they both knew the ten worthless pieces of paper solved nothing, that the bail money would not bail out the poet, that January was not the end, but only the beginning . . .

The twenty thousand in question now didn’t seem like a big deal, either, and the twelve months in jail . . . well, what’s a year in jail? Noth- ing. He’d done it himself.

“He got off easy,” he said to Mariola and tossed the paper aside. “What’s a year compared to eight! I bet the prosecutor and the judge were fans . . .”

Indeed. The prosecutor, one Manyo Genkov, really had tried his best: instead of asking for the minimum three-year sentence he had pleaded for a year, and the judge had groaned with hasty relief and banged his gavel. And as Sheytanov sat there amid the Kilifarevo forests, he likely wished for nothing more than to have been inside that courtroom, sling- ing jokes at the poet to cheer him up, shouting: “Milev! I disagree with the ruling. This man is making a mockery of your work. Only a year for that poem?! For shame! These people aren’t taking you seriously, Milev. You should’ve been hit with the maximum for writing that fine piece!” Or something in that vein.

But who could’ve possibly told him that while he read the now three-day-old newspaper, the poet had already been summoned for an “informal inquiry” in connection with his now seemingly settled case?

And how could he have known that the poet wasn’t summoned to the courthouse as he should have been—but to the Police Directorate?

And that was that.

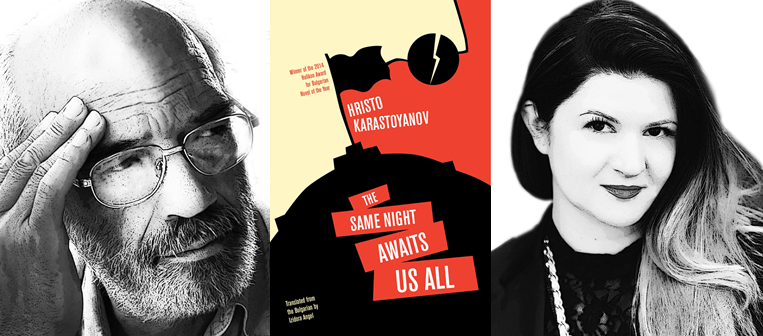

Hristo Karastoyanov is a multi-award winning contemporary Bulgarian novelist, playwright, and political essayist whose work has been translated into English, Turkish, and German. All seven of his novels have been shortlisted for the prestigious Helikon Award.

Izidora Angel is a Bulgarian-born writer and translator. She has written essays and critique in English and Bulgarian for the Chicago Reader, Publishing Perspectives, Banitza, Egoist, and others. She received a grand from English PEN for her work on The Same Night Awaits Us All.

This excerpt from The Same Night Awaits Us All is published by permission of the Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2014 by Hristo Karastoyanov. Translation copyright © 2018 by Izidora Angel.

Published on December 6, 2017.