Establishing a Global Socioeconomic Network and Data Warehouse to Monitor and Explain Health Inequalities

This is part of our special feature, Public Health in Europe.

Health

inequalities by socio-economic position (SEP) are pervasive across time and geography,

over the life-span and for most health outcomes. In the OECD countries, the gap

in life expectancy between high and low-educated people is eight years for men

and five years for women at age twenty-five years, and 3.5 years for men and

2.5 years for women at age sixty-five (Murtin et al., 2017). In the EU alone, an excess of more than

700,000 deaths per year and 33 million cases of ill health are found among

those below the highest educated groups, and such health inequalities are

estimated to cost the EU 141 billion euros in economic losses annually (Murtin

et al., 2017).

Data on social inequalities in health are at present most extensive and thoroughly analysed in Western Europe (Eikemo & Mackenbach 2012; Mackenbach et al., 2008)) and North America (The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission, 2009). The World Health Organisation Commission on Social Determinants of Health (Marmot, 2008) reported on how people from lower status socio-economic groups have higher rates of mortality and morbidity in all parts of the world. These health inequalities begin to emerge during childhood and, despite improvements in recent decades in mortality rates in infants and children up to five years old, significant inequalities in these rates exist within and between countries.

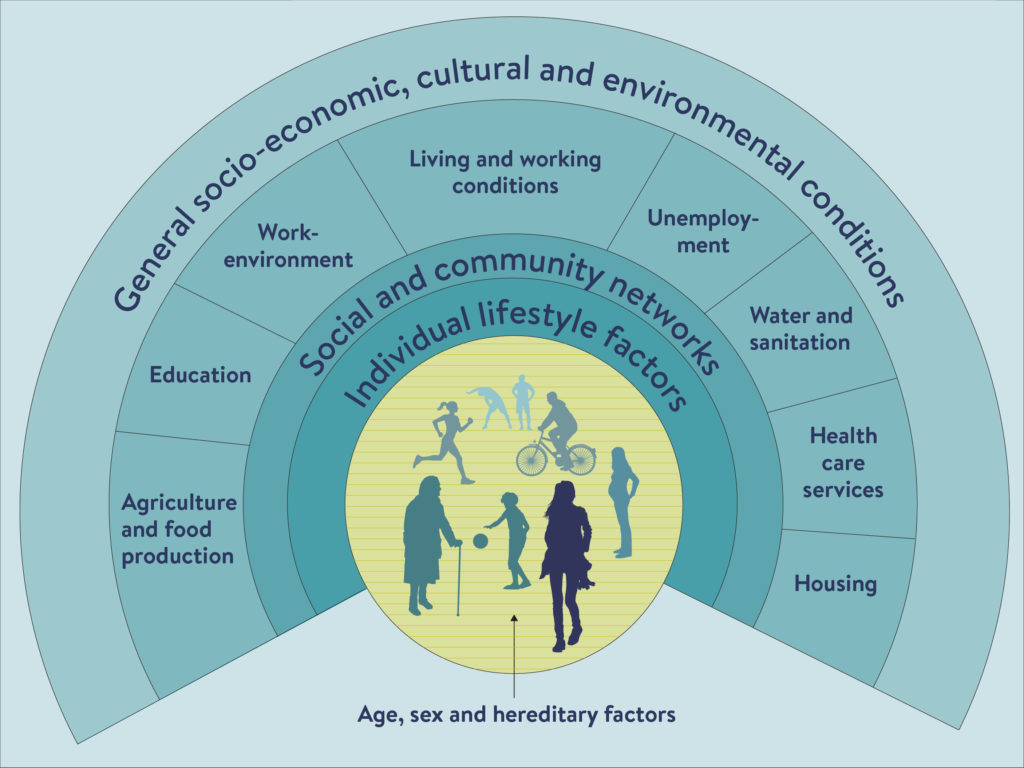

We also know that social and economic factors embedded in societal structures are key drivers of these inequalities. The roots of health inequalities are placed in “the circumstances in which people grow, live, work, and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness.” This is what we refer to as the social determinants of health (Marmot, 2006). The main material and lifestyle factors that are driven by the social determinants of health are access to essential goods and services (specifically water and sanitation, and food), housing and the living environment; lifestyle factors (such as smoking), access to health care, employment and social security, good working conditions, and transport (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991; see Figure 1).

The fact that inequality kills at a large scale highlights an urgent need to monitor the extent of health inequalities in the world, explain their causes, and identify policies, institutional conditions and interventions with the greatest impact for reducingthem. Monitoring, explaining and reducing health inequalities in the world are the three main research objectives of the Centre for Global Health Inequality Research (CHAIN), based at the Norwegian University for Science and Technology (NTNU). CHAIN is a historic collaboration between leading academic institutions (such as Erasmus University Medical Centre, Institute for Health Metrix and Evaluation (IHME), the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bocconi University, Geneva University Hospitals, and Newcastle University) and international organizations (such as UNICEF and the WHO), which has attracted world leading health inequality researchers to provide essential evidence of importance to UN member state governments across the global North and the global South.

The central concept of CHAIN is that local, regional, national and international efforts to reduce inequalities in health will continue to fail unless we drastically improve a monitoring system that allows us to track the contribution of low SEP as a global determinant of preventable morbidity and early mortality. The ongoing epidemiologic transition in the global disease burden from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which is strongly socially patterned (McNamara et al. 2017), makes it an urgent task to improve global systems for monitoring the socially stratified pattern of health and disease.

In this article, we present our plans for a global data warehouse, which will enable us to monitor socioeconomic inequalities in health through time and space and which will serve as the basis for new research on explaining and reducing health inequalities: the Global Burden of Health Inequalities data warehouse (GBHI). The work on the GBHI will be structured around a Global Socioeconomic Network, coordinated by CHAIN, for which we seek collaborators.

Figure 1: Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) model of the determinants of health

The Global Burden of Health Inequalities (GBHI) data warehouse

The GBHI data warehouse will compile and provide access to individual-level data on inequalities in health (mortality and morbidity), by socioeconomic position and (where available) by their determinants (material living conditions, behavioural risk factors, and access to healthcare) in as many countries as possible, covering all world regions. In previous research conducted by CHAIN and its collaborators, we have established harmonized databases for many countries in the global North. This research has shown that socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality are substantial within all studied countries, but with important variations in magnitude between countries (Mackenbach et al., 2008; Eikemo & Mackenbach, 2012).

Although there is abundant evidence that socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality also exist in other parts of the world, we do not know their exact magnitude because available data sources have not been harmonized and exploited.

Based at the Institute for Health Metrix and Evaluation (IHME) the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD Study) is the world’s largest systematic, scientific effort to quantify the magnitude of health loss from all diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and geographic location over time. The study has provided vital information on morbidity, mortality, and risk factors for many countries in the world (GBD 2017 Mortality Collaborators, 2018). An aggregate socio-demographic index on country and area level is a key feature of the study and analyses. However, within-country or area variation in socioeconomic position based on individual-level data is not yet fully incorporated. This calls for further analysis of the importance of low socioeconomic position as a global determinant of morbidity and mortality to inform development of effective policy solutions. Also, relative inequalities in health by education have tended to increase over time in many high-income countries (Mackenbach, 2018; Kinge et al. 2019). This development raises questions on the effectiveness of our current approaches and political willingness to manage inequalities. However, in order to be able to prioritize and exploit differences between countries regarding inequalities in health for explanatory and policy evaluation purposes, we need harmonized dataon inequalities in health and their determinants in as many countries as possible.

We will build on our experience with international, comparative studies of health inequalities in Europe, for which we have already collected and harmonized data on mortality, self-reported health problems, behavioral risk factors, and healthcare utilization, by educational level and occupational class, among the adult population of over twenty European countries, covering the 1980-2010 period (Mackenbach et al. 2018) For morbidity, we will include all internationally harmonized surveys that have included measures of socioeconomic status, health and their social determinants (including the World Health Survey (WHS), the European Social Survey (ESS), International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), the Survey of Health, Age and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), NeuroTox, EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), the GLORI platform of thirty longitudinal studies on children wellbeing (UNICEF), Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) and the US General Social Survey (GSS)), the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (UNICEF), and the Demographic and Health Surveys (MEASURE Evaluation).

Because rich data on determinants rarely exist in combination with rich data on health outcomes, CHAIN will take the lead in developing a comparable social health survey to be delivered across countries in both the global North and the global South. This part of the data warehouse will be implemented by supplementing existing social surveys around the world with special modules. We have already succeeded in introducing a module on “Health and their Social Determinants” into the European Social Survey (twenty-two countries), in South Africa (in the South African Social Attitudes Survey), in Greece (MIGHEAL), and in the US (2016 General Social Survey). CHAIN also took part of the first health survey (REHEAL) that has ever been conducted among people traveling by boat to seek asylum in Europe in six Greek refugee camps that will be utilized as well (Stathopoulou, T., et al 2019). The work on this survey was led by the National Centre for Social Research (EKKE), Athens, Greece.

For mortality, we aim to expand our existing database (from the EU-funded Demetriq project) with similar data from non-European countries, building on our experience in an on-going project conducted under the umbrella of the OECD (Mackenbach et al., 2015). For this we will rely on census-linked mortality data and on demographic and health surveys, the WHO Health for All database, as well as on UNICEF’s unique databases (for example the MICS survey), which include individual-level data from countries in all of the six world regions. Second, we will increase coverage over age by adding data on inequalities in mortality, self-reported health and health determinants among children. In Europe, some of these data can be obtained from the aforementioned data providers, but CHAIN will also aim to obtain or get access to other data sources, e.g. from the Expat Explorer Survey (HSBC) and the European Health Behaviour of School Children survey HBSC. There will be a close liaison, with a line of investigation regarding monitoring, as part of the EU funded Joint Action on Health Inequalities (2018-2021). We will further increase geographical coverage by adding data on inequalities in mortality, self-reported (or measured if available) health and health determinants among adults and children in other world regions. For high-income countries, similar data sources are available as for European countries. For low and middle income countries (LMIC), a preliminary inventory of data sources suggests the following may be suitable: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), Living Standards Measurement Survey (LSMS), World Values Survey (WVS), World Health Survey (WHS), the World Gallup Poll, the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE), the WHO Global Health Observatory (GHO) data, and data from various demographic surveillance sites.

The importance of the GBHI for next steps in global health inequalities research

Monitoring health inequalities

The GBHI data warehouse will enable us to advance research on health inequalities in all parts of the world; no single data warehouse matching the scale and completeness of the GBHI presently exists. Firstly, the GBHI data warehouse will help to monitor health inequalities across the globe in a systematic and comparable way, and better describe the role of socioeconomic position in a framework that allows for global comparison and analysis. The GBHI data warehouse will offer ample new opportunities to assess the magnitude of inequalities in health—including mortality and self-reported morbidity—in as many countries as possible, covering all world regions, and to evaluate whether they are increasing or decreasing over time.

For each combination of country, period, gender, health outcome, and level of education or occupational class (or other available measures of socioeconomic position, such as parental education) we will calculate age-standardized incidence, prevalence or mortality data. Where the data permit, we will also conduct age-specific analyses with summary measures of inequalities in health, looking at both absolute and relative inequalities.

Explaining health inequalities

Secondly, the collection and harmonization of the data in the GBHI data warehouse is a necessary first step to explain health inequalities. Importantly, the GBHI data warehouse will not only compile and provide access to individual-level data on inequalities in health and socioeconomic position, but also to data linking socioeconomic position and health inequalities. This will allow us to quantify the explanatory drivers of health inequalities as they relate to socioeconomic position and key determinants, such as environmental toxins, material living conditions, behavioural risk factors, and access to healthcare, in different countries. We hypothesise that differences in health outcomes between socioeconomic groups can be attributed to variations in exposure to the social conditions in which children and their families live and work (such as exposure to toxins, tobacco and inadequate diet, unfavourable working conditions, lack of access to healthcare, etc.).

However, the relative contributions of these conditions to inequalities in morbidity and mortality are likely to vary considerably between countries. Therefore, research across a wide range of countries is needed in order to assess the influence of the national context, e.g. different policy configurations, on how exactly the social determinants of health explain health inequalities. We will explain individual-level differences within countries by conducting analyses in which individual-level data on socioeconomic position are related to health outcomes, controlling for confounders (e.g. life style factors) and potential mediators (e.g. working conditions, living conditions etc.). Additionally, we will analyse individual-level data (e.g., on socioeconomic position and health outcomes) and aggregate-level data (e.g., on contextual factors such as social capital, mean income) simultaneously, in order to assess their independent effects. Furthermore, we will conduct ecological analyses in which countries’ magnitude of health inequalities is related to their inequality in determinants and contextual factors, taking into account aggregate-level confounders.

In each of these approaches, we will advance existing knowledge on explanations for health inequalities across countries by making full use of the global breadth of the GBHI data warehouse and by drawing on theoretical and empirical insights from Sociology, Political Science, and Epidemiology. We will employ intersectional perspectives on health inequalities to explore how social determinants of health such as socioeconomic position and gender, interact in the formation and consolidation of health inequalities (see e.g. Eikemo et al., 2018; Gkiouleka et al., 2018). This does not only offer potential explanations for the counterintuitive presence of health inequalities in generous welfare states, but also allows us to examine the impact of multiple disadvantage on health, which has been largely ignored in previous cross-national research. Additionally, we will build on some recent theoretical work on the potential of institutional approaches to inequality to explain variations in health inequalities across countries (Beckfield et al., 2017). For example, with regard to health inequalities between income groups, institutions potentially affect social inequalities in health through direct redistribution (e.g. welfare state income transfers), constraints on the wage distribution (e.g. a minimum wage), welfare services (e.g. health care) or other determinants of income (e.g. education). Seeing the role of policy configurations through an institutional lens, rather than focusing on specific policy instruments, helps to make sense of how patterns of health inequalities are shaped across a range of countries. Furthermore, while most comparative research on social inequalities in health has ignored global developments, such as the rise in bilateral trade and investment agreements, the development of digital technologies, and climate change, we can incorporate the global level in our explanatory models of health inequalities. For example, by using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods we examine how trade agreements might exacerbate social inequalities in health (see e.g. Huijts & McNamara, 2018; McNamara, 2017; e.g. trade agreements have posed restrictions to states’ capacity to reduce social inequalities in health through the regulatory environment, such as plain packaging of tobacco products).

Reducing health inequalities

Finally, the GBHI data warehouse will be important for efforts to reduce health inequalities. There is an increasing desire in many countries and at the international level to implement appropriate institutional interventions to reduce social inequalities in health. However, there is lack of accessible evidence for policymakers and practitioners about what sort of interventions are required, whether they will actually be effective in reducing social inequalities in health, and how they should be implemented. Turning this need for better evidence about interventions into action requires the identification of effective policies and interventions. Three key policy intervention areas are of particular importance here: the regulatory environment (e.g. toxin, tobacco and alcohol control, food taxation/subsidy policies, workplace regulation), healthcare policies (e.g. population coverage, funding mechanisms, service provision), and social protection policies (e.g. income maintenance, education, housing and labour market policies).

Guided by the differences in magnitude of health inequalities in different world regions and the emerging explanations of health inequalities that can be revealed by the GHBI data warehouse, researchers will be able to identify specific policy and program interventions that are effective in reducing social inequalities in health particularly amongst children and their families—in different global regions. In the longer run, the GBHI data warehouse will enable researchers to identify effective intervention programs in countries and regions with the largest health inequalities.

To achieve this, a variety of both qualitative and quantitative methodological tools can be used to study and collect best-practice examples for improving health equality, evaluate the effectiveness of these policies in different contexts by comparing countries, regions and settings, and provide recommendations for evidence-based policies for reducing inequalities in health on this basis. For example, to examine how healthcare policies can reduce inequalities in cancer incidence and cancer mortality qualitative information on policies on cancer screening can be complemented with quantitative data from the GBHI data warehouse, stratified by socioeconomic position, on cancer screening utilization and cancer mortality per each country. Such analyses could result in policy recommendations in terms of how countries can refine their screening services in order to achieve the best health outcomes within their financial means.

The Global Socio-economic network

The data warehouse will provide the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study with data that can be used to estimate the protective effects of education and other forms of SEP on preventing poor health outcomes with an ambition to facilitate future inclusions of SEP in the GBD Study. A long-term goal of CHAIN and the GBHI is to strengthen the analysis of SEP in other large-scale global health research endeavors. The developing collaboration with the Global Burden of Disease study is an important step towards that goal, and an important means to increase utility of the work.

The completeness of the GBHI will largely depend on the collaboration within our Global Socioeconomic Network, for which we are seeking collaborators who can inform us about relevant data sources and otherwise support our work with their expertise. CHAIN collaborators will be given access to our non-sensitive harmonized data.

Challenges and limitations

The collection and harmonization of survey data for the GBHI data warehouse is not a straightforward task, also because data of this type are not readily available in the developing world. This will be challenge, but also a unique contribution.

In addition, recent evidence suggests that different cross-national surveys may not always yield similar results when it comes to the presence and level of health inequalities across countries (Rubio-Valverde, Nusselder & Mackenbach, 2019; Toch-Marquardt, 2017). This needs to be taken into account as much as possible in the harmonization of the various survey data sources that are collected in the GHBI data warehouse, especially given that these differences across surveys cannot be fully explained by variations in survey characteristics such as response rates, sampling designs and data collection modes, or by differences in the operationalization of key variables. We will therefore draw upon the broad experience of the GBD in adjusting data for known biases, including rigorous treatment of estimate uncertainties.

Nevertheless, further analysis of why exactly the observed patterns of health inequality vary across surveys could deliver results that would be of great use to all researchers using cross-national survey data to analyse health inequalities. Therefore, in addition to collecting and harmonizing survey data, the GBHI data warehouse can also take a leading role in advancing our knowledge of the comparability of survey data sources on health inequalities, for example by mapping the exact differences in design and operationalization between surveys and by assessing the impact these differences will have on estimates of health inequalities. In other words, the GBHI data warehouse will not only “house” survey data as such, but it would also facilitate the creation of world-leading expert knowledge about how to use these data most effectively. Moreover, in addition to being a central resource for researchers analysing health inequalities with cross-national survey data, the GBHI data warehouse will also be able to play a crucial role in assessing the exact possibilities, challenges and lessons for future development of new surveys that include measures of health and its social determinants.

Terje Andreas Eikemo (PhD) is a professor of Sociology at the Norwegian University for Science and Technology (NTNU), where he leads CHAIN: Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research. Moreover, Eikemo`s research focus has been to explain differences in mental and physical health, chronic diseases and mortality within and between countries world-wide. He has examined the contribution of welfare policies, social, economic and material factors, life style factors (such as smoking, alcohol, physical activity and diet), childhood conditions, working conditions, unemployment, housing conditions and health care. He has led the development of specialist modules for several health surveys in the world (for example for the European Social Survey) and he has received several awards for his research. Eikemo is the current Editor-in-Chief of the Scandinavian Journal of Public Health.

Johan Mackenbach received a Medical Doctor’s degree and a PhD in Public Health from Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. He is also a registered epidemiologist and public health physician. He is Professor of Public Health of the Department of Public Health at Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, the Netherlands. His research interests are in social epidemiology, medical demography, and health services research. He is former editor-in-chief of the European Journal of Public Health, and has coordinated a number of international-comparative studies funded by the European Commission. His research focuses on socioeconomic inequalities in health, on issues related to aging and compression of morbidity, and on the effectiveness and quality of health services. He is actively engaged in exchanges between research and policy, among others as a member of several government advisory councils in the Netherlands.

Simon Øverland (PhD) is Director of the Centre for Disease Burden at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and Professor at University of Bergen, Norway. His main research interests is in epidemiology and public health, in particular related to burden of disease, and health in relation to work ability, unemployment and sickness absence, mortality, care and co-morbidities. Dr. Øverland has wide research experience ranging from clinical trials, to leading roles in translating research to policy. Amongst ongoing projects, Dr. Øverland is PI on a large registry-based study set up to examine social and regional differences in disease burden, and is work package leader on a recently awarded grant led by CHAIN.

Mirza Balaj is the Research Coordinator of CHAIN. She has a PhD in Sociology from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Balaj’s research explores how the interaction of various mechanisms at the structural, social and individual level can explain the persistence of health inequalities and the differences in the magnitude of inequalities within countries. She has developed part of her work within two NORFACE projects – ‘Health Inequalities in European Welfare States (HiNEWS)’ and ‘The Paradox of Health State Futures (HEALTHDOX)’ – and published in e.g. European Journal of Public Health, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health.

Tim Huijts (PhD) is project leader and researcher at the Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market (ROA) at Maastricht University, the Netherlands. In his research he examines how national and institutional factors influence social inequalities, and particularly social inequalities in health. His work has appeared in a broad range of journals in Sociology, Demography and Public Health. He was a co-investigator on the NORFACE-funded project on ‘Health inequalities in European welfare states’ (HiNews), and a co-applicant for the rotating module on ‘Social inequalities in health and their determinants’ for the 7th wave of the European Social Survey. His research was recently recognized with a Philip Leverhulme Prize (2017) for outstanding achievement.

Emmanuela Gakidou, MSc, PhD, is Professor of Health Metrics Sciences and Senior Director of Organizational Development and Training at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. She is also a Faculty Affiliate for the Center for Statistics and the Social Sciences at the University of Washington. Dr. Gakidou’s research interests focus on impact evaluation, methods, and tools development for analytical challenges in global health. Examples of current research projects include the evaluation of community-based interventions to improve non-communicable disease management in underserved populations, the assessment of facility efficiency in the provision of health services, and the measurement of poverty and educational attainment at the small area level. Before joining IHME, Dr. Gakidou was a research associate at the Harvard Initiative for Global Health and the Institute for Quantitative Social Science. Prior to moving to Harvard University, Dr. Gakidou worked as a health economist at the World Health Organization (WHO), where she led work on the measurement of health inequalities.

References

Beckfield, J., Balaj, M., McNamara, C., Huijts, T., Bambra, C. & Eikemo, T. (2017). The health of European populations: introduction to the special supplement on the 2014 European Social Survey (2014) rotating module on the social determinants of health. European Journal of Public Health, 27, 3-7.

Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M. (1991) Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for Futures Studies.

Eikemo, T.A., Mackenbach, J.P. (2012). The potential for reducing health inequalities in Europe. EURO-GBD-SE Final Report. Rotterdam: Department of Public Health, University Medical Centre Rotterdam.

Eikemo, T., Gkiouleka, A., Rapp, C., Utvei, S., Huijts, T. & Stathopoulou, T. (2018). Non-communicable diseases in Greece: inequality, gender and migration. European Journal of Public Health, 28, 38-47.

GBD 2017 Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 8 Nov 2018;392:1684-735.

Gkiouleka, A., Huijts, T., Beckfield, J. & Bambra, C. (2018). Understanding the micro and macro politics of health: inequalities, intersectionality & institutions – a research agenda. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 92-98.

Huijts, T. & McNamara, C. (2018). Trade agreements, public policy and social inequalities in health. Global Social Policy, 18, 88-93.

Kinge JM, Modalsli JH, Øverland S, et al. Association of Household Income With Life Expectancy and Cause-Specific Mortality in Norway, 2005-2015. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1916–1925.

Mackenbach, J. P., Valverde, J. R., Artnik, B., Bopp, M., Brønnum-Hansen, H., Deboosere, P., … Nusselder, W. J. (2018). Trends in health inequalities in 27 European countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(25), 6440-6445.

Mackenbach, J.P., Menvielle, G., Jasilionis, D., de Gelder, R. (2015). Measuring educational inequalities in mortality statistics. Paris: OECD.

Mackenbach, J.P., Stirbu, I., Roskam, A.J., Schaap, M.M., Menvielle, G., Leinsalu, M., et al. (2008). Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 2468-2481.

McNamara, C.L., Balaj, M., Thomson, K.H., Eikemo, T.A., Solheim, E.F., & Bambra, C. (2017). The socioeconomic distribution of non-communicable diseases in Europe: findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. European Journal of Public Health. 1;27(suppl_1): 22-26

Marmot, M. (2006) Introduction, In Marmot M and Wilkinson, R.G. (eds) Social Determinants of Health Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-5.

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, Commission on Social Determinants of H. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661-9.

McNamara, C. (2017). Trade liberalization and social determinants of health: a state of the literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 176, 1-13.

Murtin, F., et al. (2017), “Inequalities in longevity by education in OECD countries: Insights from new OECD estimates”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2017/02, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America. Beyond Health Care: New Directions to a Healthier America: Recommendations from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America. Princeton, 2009.

Rubio-Valverde, J. R., Nusselder, W.J. & Mackenbach, J.P. (2019). Educational inequalities in Global Activity Limitation Indicator disability in 28 European countries: does the choice of survey matter? International Journal of Public Health, 64, 461-474.

Stathopoulou, T., Avrami, L., Kostaki, A., Cavounidis, Eikemo, T.A. (2019). Safety, Health and Trauma among Newly Arrived Refugees in Greece. Journal of Refugee Studies, doi:10.1093/jrs/fez034

Toch-Marquardt, M. (2017). Does the pattern of occupational class inequalities in self-reported health depend on the choice of survey? A comparative analysis of four surveys and 35 European countries. European Journal of Public Health, 27, 34-39.

Photo: Contrast different bright human watercolor painting design | Shutterstock

Published on June 11, 2019.